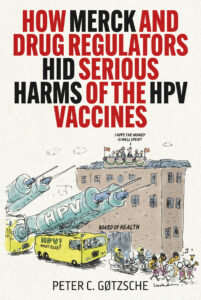

How Merck and drug regulators hid serious harms of the HPV vaccines

My book will be published on 19 August by Skyhorse in New York (288 pages). It can be pre-ordered here.

My book will be published on 19 August by Skyhorse in New York (288 pages). It can be pre-ordered here.

Book description

This is a story of scientific misconduct, committed by Merck, the fourth biggest drug company in the world. Merck has committed scientific misconduct before, and the author describes the fraud related to Merck’s arthritis drug, Vioxx, which killed tens of thousands of patients because Merck concealed that it causes heart attacks.

In his role as an expert witness in a lawsuit against Merck, Dr. Peter C. Gøtzsche read 112,452 pages of confidential study reports about Merck’s HPV vaccine Gardasil, corresponding to 500 medium-sized books, and wrote an expert report of 350 pages with four appendices. Dr. Gøtzsche reveals that Merck used numerous tactics to avoid reporting serious neurological harms of Gardasil, including Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), which, in his view, in some cases constituted outright fraud.

How Merck and Drug Regulators Hid Serious Harms of the HPV Vaccines details how the drug agencies were complicit in scientific misconduct and gives many examples that other authorities also provided seriously misleading information about the benefits and harms of the HPV vaccines.

Dr. Gøtzsche gives a rare insight into the behavior of drug company lawyers when a company comes under attack for having concealed serious harms of its drug. He describes how he was harassed by Merck’s lawyer who tried to impugn his character and scientific credibility in ways, which included setting up traps for him during his deposition. If anyone was in doubt whether Merck and our authorities can be trusted, this book gives the answer.

Peter C. Gøtzsche Is professor emeritus, physician, and a bestselling book author. His scientific works have been cited over 190,000 times. He is the only Dane who has published over 100 papers in “the big five” journals (BMJ, Lancet, JAMA, Annals of Internal Medicine, and New England Journal of Medicine). He has also appeared on The Daily Show. He currently works as a researcher, lecturer, author, independent consultant, expert witness in lawsuits, and produces films and interviews, in collaboration with Danish award-winning filmmaker and historian Janus Bang.

Withdrawal symptoms are not relapse of the disease: A patient’s view on how psychiatry mislabels neurochemical rebound

By Martin Hemberger

Diplom Wirtschaftsinformatiker (FH)

Würzburg, Germany

A dangerous misconception, deeply embedded in psychiatry, is that the return of symptoms after discontinuing psychiatric medication is a relapse of the original condition. For many patiens, including me, this belief has led to misdiagnosis, suffering, and unnecessary, prolonged exposure to harmful drugs. What psychiatry labels as “relapse” is almost always a physiological response to the cessation of a substance that has altered brain functions. Read full article

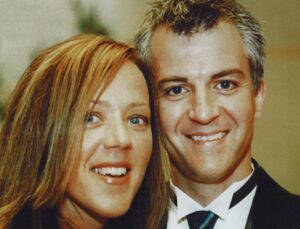

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Woody Witczak

In 2003, Tim, known to most as Woody, died of a sertraline-induced suicide at age 37. He was not depressed, nor did he have any history of mental illness. He died after taking the drug for five weeks with the dosage being doubled shortly before his death. He was given the antidepressant by his general physician for “insomnia.”

In 2003, Tim, known to most as Woody, died of a sertraline-induced suicide at age 37. He was not depressed, nor did he have any history of mental illness. He died after taking the drug for five weeks with the dosage being doubled shortly before his death. He was given the antidepressant by his general physician for “insomnia.”

Woody loved life and all that this world has to offer. He had endless energy, a constant smile and truly cared for others. He had a successful career in sales and was active in the community, socially and politically, always willing to fight against injustice. Woody truly inspired others to be the best they could be.

Woody went to his regular internist because he was having trouble sleeping, in part because he had just started a new position as vice president of sales with a start-up company about two months earlier. He was excited about this dream opportunity to make his mark on the business world. Along with this excitement came some stress and difficulty sleeping.

This was the first time he’d ever gone to a doctor for this sort of issue. Woody’s doctor gave him three weeks’ worth of sertraline samples and told him to come back for a follow-up appointment after the samples were finished. There was no discussion about the risks or the need to be closely monitored because of this mind-altering drug. The first three weeks Woody was taking sertraline his wife was out of the country on business and no one was monitoring him. Within a couple of days, he experienced many of the known side effects of sertraline, e.g. night sweats, diarrhoea, trembling hands, and worsened anxiety.

One of the most significant side effects Woody had was akathisia. He was very restless, which caused him not to sleep, and irritable and felt he always needed to keep moving.

Shortly before his death, Woody came home crying after driving around all day. He sat in a foetal position on the kitchen floor profusely sweating with his hands pressing around his head saying, “Help me. Help me. I don’t know what’s happening to me. I am losing my mind. It’s like my head is outside my body looking in.” The next day, Woody called his doctor to tell him what happened and was told to be patient because it could take four to six weeks before the drug worked.

Over the course of the next week, in typical Woody fashion, he was looking for ways to “beat this feeling in my head all while still running three to four miles a day. Two weeks later, when sertraline should have worked according to his doctor, Woody was found hanging from the rafters in the garage. Woody’s family and friends only wish they knew then what they know now. It wasn’t Woody’s head. It was the drug.

Never once did Kim, Woody’s wife, or Woody question the drug. Why would they? It was FDA approved, heavily promoted as safe and effective, and it was given by his doctor. People trust their doctors, who assume the FDA and the drug companies did their job to ensure that the drugs they prescribe are safe and effective.

The day Woody died, the front page of the local newspaper had an article that people in the UK had found a link between antidepressants and suicide in teens. Kim’s quest for the truth has led her to testify about the dangers of SSRIs at hearings in the US Senate, at the FDA, the Health Department, Congress and the courts. Together with other campaigners, she was active in getting black box warnings added to antidepressants.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Cecily Bostock

Cecily Bostock was a musician, an artist, an over-achiever in almost everything she did. She was having a lot of trouble sleeping, had racing thoughts, was over-analysing, and was overly sensitive. This prompted a prescription of paroxetine.

Cecily Bostock was a musician, an artist, an over-achiever in almost everything she did. She was having a lot of trouble sleeping, had racing thoughts, was over-analysing, and was overly sensitive. This prompted a prescription of paroxetine.

Her mother Sara said that within three weeks of taking Seroxat, Cecily became a totally different person.

“The last two days she was just a complete zombie I have to say. She was just agitated, jumping at every noise and not making sense. I was very concerned. We were very close to Cecily. I just loved her deeply.”

Sara found her daughter lying on the kitchen floor. There was a large chef’s knife on the floor by her and just a trickle of blood from her chest. Cecily had stabbed herself twice through the heart. Her autopsy revealed she had a very high blood level of paroxetine, which reflects poor metabolisation and is a feature common to many of these suicides.

Cecily killed herself about 20 days after she had started taking Seroxat. She was just 25 years old.

Since her daughter’s death, Sara has been campaigning and creating awareness about the dangers of antidepressants. She spoke at a charity conference in 2008 about her experience and knowledge from years of research, which is on video (http://vimeo. com/16727219). Sara has also given testimony at an FDA hearing and has co-founded www.ssristories.com, which is a collection of over 5,000 stories that have appeared in the media.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Candace Downing

Candace was a happy 12-year-old girl who had never been depressed or had suicidal ideation. She was prescribed sertraline because she suffered from school anxiety. Her mother Mathy found her beautiful little girl hanging, her knees drawn up. Her father knew the minute he saw her that it was too late but tried to administer CPR, which continued for another 45 minutes at the hospital but in vain.

Candace was a happy 12-year-old girl who had never been depressed or had suicidal ideation. She was prescribed sertraline because she suffered from school anxiety. Her mother Mathy found her beautiful little girl hanging, her knees drawn up. Her father knew the minute he saw her that it was too late but tried to administer CPR, which continued for another 45 minutes at the hospital but in vain.

“Do you know what that’s like, to see your happy little girl hanging? There was no note, no warning, not for her, not for us.”

When Candace entered middle school, she began having problems on tests and frustration over certain homework assignments. She would block on answers she knew on tests, or write so illegibly that some answers were marked incorrect, even if she had them correct. Because of her parents’ concern, she saw her paediatrician, who recommended that she see a child psychiatrist. He immediately wanted to give her sertraline. Mathy was opposed, but he reassured her that it was safe and that he would recheck her in three weeks. After three weeks, he wanted to double the dose, from 12.5 mg to 25 mg, which Mathy opposed. Because of her vehemence, the medication was not increased at that time.

Right before school started following summer vacation, Mathy and Candace returned to the child psychiatrist, who once again wanted to increase the dose. When Mathy voiced concern, he stated, “What are you worried about? Kids take 100-200 mg of Zoloft a day without any problems.”

“Why was so much hidden from us? Why were we not ever informed about the contraindications or adverse reactions of Zoloft, or for that matter, antidepressants in children? Didn’t we have the right to be informed? … Shouldn’t it have been our choice to place Candace on medications that involved risk rather than the pharmaceutical companies or the FDA?”

Candace had many friends. Everybody loved her and when she died, more than a thousand people attended her service. Candace was everybody’s little girl, and if it could happen to her, it could happen to anyone’s child.

After Candace’s death, the Downings became aware that an abrupt withdrawal from an antidepressant can prove fatal, as it can create psychotic states, with decreased powers of reasoning. No one ever told them that their daughter was going in and out of psychotic states and needed to be watched closely every second.

“If we had been able to make our own choices, if we had been aware of the risks, this would never have happened, as we would never have allowed Candace to be placed on such a risky and controversial medication,” said Andrew Downing.

“What happened to our daughter and so many others like her is a travesty. We have since met other families who have lost their child after Zoloft was prescribed for test anxiety. Those in a position to create positive change can go home to their children at night. We will never have that opportunity with Candace again. Our therapist referred to what happened to Candace as abduction. She was taken away from us with no warning and died in the process. What gave them that right?” Mathy stated tearfully.

The Downings, and other families, charge that drug makers knew from premarketing studies that these drugs made some children and teens suicidal but hid the study results.

“This is about the right of the American people to make their own decisions. I can’t sit back as an American citizen and watch children continue to die. And that is why we hope the documentary “Prescription: Suicide?” will help to get that message out where it counts: among the American families whose biggest concern is to protect and nurture their children,” said Mathy.

The Downings have testified at FDA hearings and are lobbying Congress to make all research public. Mathy has also addressed the US Drug Safety Systems Committee, which is reviewing the numerous allegations against the FDA’s inadequate handling of policy regarding antidepressants.

The Downings’ psychiatrist had not told them that he was on Pfizer payroll making speeches touting Zoloft. Pfizer said in a statement for CBS News that “it’s paid consulting work with doctors helps the company learn how to reduce adverse reactions.” No condolences were apparently offered.

People have called the Downings and said that because of Candace their child is alive, as they knew what to look for.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Stewart Dolin

Stewart Dolin had the perfect life. He was married to his high school sweetheart for 36 years. He was the father of two grown children with whom he had a very close and meaningful relationship. He was a senior partner of a large international law firm, managing hundreds of corporate lawyers. He enjoyed his work and derived satisfaction from cultivating relationships with his clients, as well as helping them achieve the results they desired. He enjoyed travel, skiing, dining, joking around with his family and friends and an occasional cigar. He was 57 years old and high on life.

Stewart Dolin had the perfect life. He was married to his high school sweetheart for 36 years. He was the father of two grown children with whom he had a very close and meaningful relationship. He was a senior partner of a large international law firm, managing hundreds of corporate lawyers. He enjoyed his work and derived satisfaction from cultivating relationships with his clients, as well as helping them achieve the results they desired. He enjoyed travel, skiing, dining, joking around with his family and friends and an occasional cigar. He was 57 years old and high on life.

In the summer of 2010, Stewart developed some anxiety regarding work. He was prescribed paroxetine. Within days, Stewart’s anxiety became worse. He felt restless, had trouble sleeping and kept saying, “I still feel so anxious.”

Six days after beginning the medication, following a regular lunch with a business associate, Stewart left his office and walked to a nearby train platform. A registered nurse later reported seeing Stewart pacing back and forth and looking very agitated. As a train approached, Stewart took his own life. This happy, funny, loving, wealthy, dedicated husband and father who loved life left no note and no logical reason why he would suddenly want to end it all. The package insert for paroxetine did not list suicidal behaviour as a potential side effect for men of Stewart’s age.

Stewart’s wife did not know it then, but Stewart was suffering from akathisia. She started MISSD (The Medication-Induced Suicide Education Foundation in Memory of Stewart Dolin), which is a non-profit organisation dedicated to honouring the memory of Stewart and other victims of akathisia by raising awareness and educating the public about the dangers of akathisia so that needless deaths are prevented.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Shane Clancy

Shane was 22 years old when he broke up with his girlfriend. He found it difficult without her and was prescribed citalopram. He became agitated and rang the doctor four days later, as his tongue felt very swollen (a recognized side effect of citalopram). He left a message but got no response, and five days later he took the remainder of the tablets in an attempted suicide.

Shane was 22 years old when he broke up with his girlfriend. He found it difficult without her and was prescribed citalopram. He became agitated and rang the doctor four days later, as his tongue felt very swollen (a recognized side effect of citalopram). He left a message but got no response, and five days later he took the remainder of the tablets in an attempted suicide.

His mother brought him back to the clinic where he saw a different doctor who continued the prescription for citalopram.

Ten days later, Shane called his ex-girlfriend, who was in her new boyfriend’s house, and asked her to send her boyfriend outside, as Shane was hurt and needed help. Shane stabbed the boyfriend fatally and also stabbed his ex-girlfriend and her boyfriend’s brother who emerged from the house to find out what was going on. Shane was later found dead in the garden having stabbed himself about 20 times.

The case was all over the media for several days and every scrap of evidence that pointed to pre-meditation was a nail in Shane’s coffin. At first there was no mention of antidepressants, but Leonie Fennell, Shane’s mother, feeling guilty for having engineered her son onto citalopram, raised the issue. The Irish College of Psychiatrists responded that there was absolutely no evidence that antidepressants could cause problems and to say so was dangerous and irresponsible.

Before the inquest, an extraordinary letter to the national newspapers was sent from all professors of psychiatry in Ireland (or so they said), stating that there was no evidence that antidepressants could cause harm.

The jurors were asked to recommend whether the verdict should be suicide or an open verdict. An open verdict means that there is no clear evidence that the act was planned, but could, for example, have happened under the influence of a substance like LSD. In European countries, an open verdict is not an initial step to suing a pharmaceutical company, as it is almost impossible to sue a pharmaceutical company in Europe.

Returning an open verdict in England or Ireland does not blame the drug. It simply means in this case that the jurors have decided that the killings and the events did not permit a straightforward answer. But even so, the pharmaceutical companies sent academics such as Professor Guy Goodwin from Oxford, along with several high-powered lawyers to ensure the coroner or the jury would return a suicide verdict. It didn’t. David Healy provided expert testimony and the jury returned an open verdict.

Just like the American Psychiatric Association (APA) before and since, The Irish College of Psychiatrists went into overdrive issuing statements left, right, and centre that there was no evidence that citalopram could cause suicide or violence. This led a retired professor of psychiatry, Tom Fahy, send this letter to the Irish College:

“I am afraid the College is plain wrong. There is no such thing as a college statement which is circulated to the membership simultaneous with its publication, without opportunity for comment or vote and ‘in unison’ with a body 100% financed by drug companies, and with personal hostile references to expert testimony at an inquest with families still in grief. And this on the heels of a dreadful multiprofessorial letter even before the inquest began. Extraordinary and outside my experience. If I were not retired I’d dissociate and publicly resign.”

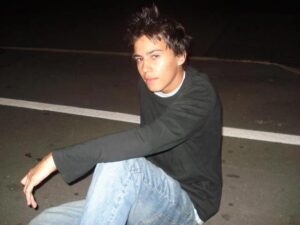

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Jake McGill Lynch

Jake’s mother, Stephanie, describes her son as a beautiful, bright 14-year old boy. In late 2011, he was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome in an extremely mild form (the diagnosis of Asperger’s was eliminated in 2013 in DSM-5 and replaced by a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder).

Jake’s mother, Stephanie, describes her son as a beautiful, bright 14-year old boy. In late 2011, he was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome in an extremely mild form (the diagnosis of Asperger’s was eliminated in 2013 in DSM-5 and replaced by a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder).

Jake started counselling with a psychologist in 2011 due to some dark thoughts that had appeared in an essay he wrote in school. In January 2013, he had counselling again, for anxiety, and his psychologist decided to refer him to her colleague, a psychiatrist, as she felt his anxiety would be heightened when he was to sit his state exams. Jake’s parents didn’t even know what a psychiatrist was but just thought it was the psychologist’s colleague.

Jake’s dad took him to his appointment because no big deal was made of it, and they met with the psychiatrist for ten minutes, after which they left with a prescription for fluoxetine. Jake had never been on medication before, but the family was not given any literature or any description from the psychiatrist or the pharmacist, and they didn’t even know what sort of drug Prozac was but simply trusted the psychiatrist.

Six days later, Jake had his first reaction. He walked out of an exam half-way through it and cried for about 2-3 hours that night, saying, “You don’t know what it’s like in my head.” His parents thought this was from the stress of the exams. They never imagined that a drug could do this to a person.

About a week later, they got Jake back to the psychiatrist and told her all about what happened, but she said that it would wear off after three or four weeks and that Jake would be fine. But Jake was not fine, and on day 46 he was a bit restless after school and looked a bit flush in the face, although he never had a colour in his cheeks. His parents thought he had a row with his little online girlfriend.

The family had a legally held rifle in the house, as Jake and Stephanie were members of a shooting club. They would often take the gun down, and Jake asked if he could take it down that night, which was nothing out of the ordinary, so his request was granted. Stephanie forgot to take the box from his room with bolt and ammunition.

Jake placed the gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger. He had no history of suicide ideation or self-harm, and no diagnosis of anything but Asperger’s. However, the National Health Service in Ireland is now trying to say he had severe anxiety – although this isn’t true – and it fights the parents from every corner with this. It is the same story all the time: put all the blame on the disease, never on the drug. The parents asked David Healy to do a second opinion based on Jake’s medical files, which he did.

Stephanie and her husband have attended their son’s inquest three times so far and are still in the middle of a legal argument about which medical expert the Coroner’s court will allow them to consult. The court has refused their request to use David Healy, as he is considered to be not impartial due to his papers and books about the relation between SSRIs and suicide!

Stephanie finds the whole thing absolutely disgusting. This was a 14-year old child who had plans for the future. He had no illness, he had a condition that no medication would fix, and he was living quite happily with just counselling for his anxiety. Stephanie and her husband were never told about the dangers of drugs like fluoxetine. Had they known about them, they would never have kept a firearm in the house.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Toran Bradshaw

Maria Bradshaw’s son Toran who was her only child was prescribed fluoxetine in January 2007 despite having been assessed as being a healthy adolescent who had an expected reaction to a stressful life event, which was a breakup with his girlfriend. A month later, Toran experienced a severe cluster of adverse reactions including suicidal behaviour, self-harm, aggression, hostility, hallucinations, lack of concentration and impaired functioning. The symptoms were so severe that he dropped out of school. His psychiatrist’s response was to increase his dose, which worsened the adverse reactions. Toran withdrew from fluoxetine and from mental health treatment of his own volition.

Maria Bradshaw’s son Toran who was her only child was prescribed fluoxetine in January 2007 despite having been assessed as being a healthy adolescent who had an expected reaction to a stressful life event, which was a breakup with his girlfriend. A month later, Toran experienced a severe cluster of adverse reactions including suicidal behaviour, self-harm, aggression, hostility, hallucinations, lack of concentration and impaired functioning. The symptoms were so severe that he dropped out of school. His psychiatrist’s response was to increase his dose, which worsened the adverse reactions. Toran withdrew from fluoxetine and from mental health treatment of his own volition.

The following year, a psychiatric registrar prescribed fluoxetine to him again, against his mother’s wishes. The registrar recorded no diagnosis after having conducted a mental state exam and finding no evidence of depression, anxiety or any other mental disorder. The next day, a multi-disciplinary team reviewed Toran’s file and recorded “diagnosis deferred” noting that there was no evidence of a mental disorder. Toran initially refused the prescription on the basis that fluoxetine should not be taken with alcohol, but the registrar recorded that he had reached an agreement with Toran that he would stop taking the fluoxetine on a Friday, could drink up to six bottles of beer a night over the weekend and restart his fluoxetine on Mondays. Given fluoxetine’s long half-life in the body, 2 to 4 days for the drug and 7 to 15 days for its active metabolite norfluoxetine, this was a foolish recommendation. Toran followed this regime but suffered a repeat of the former adverse reactions and suddenly hanged himself after 15 days on fluoxetine. He was only 17 years old.

After Toran’s death, Maria had genetic testing conducted, which confirmed that Toran metabolised drugs slowly and had therefore been overdosed. Maria also established CASPER, an organisation where those bereaved by suicide help others bereaved by suicide (http://www.casper.org.nz/). Maria has told me that the national media have credited CASPER with a 20% drop in youth suicide and that it means more to her than anything else that her son continues to do good in the world despite not being here physically.

Maria wrote to the District Health Boards in New Zealand and found out that 8% of those who died and who had gotten a recent prescription for an antidepressant, had no diagnosis of any mental disorder. In the district responsible for Toran’s care, 75% of those under 18 who died had no diagnosis.

In New Zealand, psychiatrists and suicidologists have managed to convince the government that publishing information on suicides causes copycat suicide. She has reviewed the evidence for this, which is extremely weak, but it’s nonetheless a criminal offense for Maria to tell Toran’s story, punishable by a fine of up to $5,000 each time and a fine for the media of up to $20,000. These threats have not stopped Maria and she has had support from the media.

Maria sold her home to pay for Toran’s inquest when the doctors dragged it out over 18 days of hearings, thinking she would walk away because of the cost. She now lives in Dublin, in the home of another mother who lost her child to SSRI-induced suicide, Leonie Fennell, and has everything she owns in two suitcases.

There have been ten government enquiries into Toran’s death but, as in all such cases, the issue is not whether the child received a good standard of care but whether the psychiatrist departed from generally accepted practice. And of course, since the usual practice in psychiatry is terribly poor, most of the investigations found that Toran’s care was not a departure from usual practice. However, both the government and Mylan Pharmaceuticals have resolved that it is probable that fluoxetine caused Toran’s suicide.

Maria is still fighting to achieve justice and has persuaded the police to review Toran’s file to see whether manslaughter charges can be laid. She hopes that her efforts will be a deterrent, which could make other doctors consider that their patients may have a stroppy mother like her and be more careful. Maria has spent seven years on meticulously documenting Toran’s case learning everything she could about psychopharmacology, psychiatry, neurochemistry, genetics, randomised trials and anything else that could help not only her but also all the other parents that have stories similar to hers.

When I gave a lecture at the Department of Psychology at the Manooth University outside Dublin, to which Maria had invited me, another bereaved mother was in the audience, Stephanie McGill Lynch, who also lost her child to fluoxetine. Maria wrote to me:

“I know you agree with me that this has got to stop.” Yes, and this is why I have written this book. I won’t accept that doctors and drug companies push our children into suicide with drugs that have no benefits for them. I cannot see it’s any different to killing our children by pushing narcotic drugs in the street.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)

Case stories of suicides caused by antidepressants: Danilo Terrida

Danilo Terrida was only 20 when he hanged himself in a crane at a shipyard in 2011, two hours after having assured his family on the phone that he was fine and had small-talked with them. A month earlier, he had celebrated his birthday and everything apparently went well. Two weeks later, he made contact with the emergency medical service because he did not feel well psychologically and was sent home with tranquillising pills and was advised to see a doctor the next day. The local doctor he contacted refused to see him and asked him to call his family doctor several hundred kilometres away. This he did, and after eight minutes on the phone, he was prescribed sertraline, although he wasn’t depressed, and with no follow-up. A few moments before he killed himself, Danilo talked to a friend and said he didn’t know what was happening to him, but he didn’t mention anything about suicide. This is rather typical of an SSRI-induced suicide, and the timing is also typical. Many people kill themselves early on. The involved doctors have been officially criticised for amending Danilo’s files, up to a year after his death, so that it looked more plausible that he killed himself because of a depression, which wasn’t true (see www.daniloforlivet.dk).

Danilo Terrida was only 20 when he hanged himself in a crane at a shipyard in 2011, two hours after having assured his family on the phone that he was fine and had small-talked with them. A month earlier, he had celebrated his birthday and everything apparently went well. Two weeks later, he made contact with the emergency medical service because he did not feel well psychologically and was sent home with tranquillising pills and was advised to see a doctor the next day. The local doctor he contacted refused to see him and asked him to call his family doctor several hundred kilometres away. This he did, and after eight minutes on the phone, he was prescribed sertraline, although he wasn’t depressed, and with no follow-up. A few moments before he killed himself, Danilo talked to a friend and said he didn’t know what was happening to him, but he didn’t mention anything about suicide. This is rather typical of an SSRI-induced suicide, and the timing is also typical. Many people kill themselves early on. The involved doctors have been officially criticised for amending Danilo’s files, up to a year after his death, so that it looked more plausible that he killed himself because of a depression, which wasn’t true (see www.daniloforlivet.dk).

At least 11 other people, 10 of them adults, who have committed suicide in Denmark on antidepressants have acquired economic compensation from the Patient Insurance Association.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)