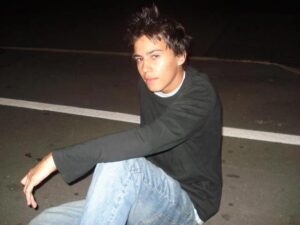

Maria Bradshaw’s son Toran who was her only child was prescribed fluoxetine in January 2007 despite having been assessed as being a healthy adolescent who had an expected reaction to a stressful life event, which was a breakup with his girlfriend. A month later, Toran experienced a severe cluster of adverse reactions including suicidal behaviour, self-harm, aggression, hostility, hallucinations, lack of concentration and impaired functioning. The symptoms were so severe that he dropped out of school. His psychiatrist’s response was to increase his dose, which worsened the adverse reactions. Toran withdrew from fluoxetine and from mental health treatment of his own volition.

Maria Bradshaw’s son Toran who was her only child was prescribed fluoxetine in January 2007 despite having been assessed as being a healthy adolescent who had an expected reaction to a stressful life event, which was a breakup with his girlfriend. A month later, Toran experienced a severe cluster of adverse reactions including suicidal behaviour, self-harm, aggression, hostility, hallucinations, lack of concentration and impaired functioning. The symptoms were so severe that he dropped out of school. His psychiatrist’s response was to increase his dose, which worsened the adverse reactions. Toran withdrew from fluoxetine and from mental health treatment of his own volition.

The following year, a psychiatric registrar prescribed fluoxetine to him again, against his mother’s wishes. The registrar recorded no diagnosis after having conducted a mental state exam and finding no evidence of depression, anxiety or any other mental disorder. The next day, a multi-disciplinary team reviewed Toran’s file and recorded “diagnosis deferred” noting that there was no evidence of a mental disorder. Toran initially refused the prescription on the basis that fluoxetine should not be taken with alcohol, but the registrar recorded that he had reached an agreement with Toran that he would stop taking the fluoxetine on a Friday, could drink up to six bottles of beer a night over the weekend and restart his fluoxetine on Mondays. Given fluoxetine’s long half-life in the body, 2 to 4 days for the drug and 7 to 15 days for its active metabolite norfluoxetine, this was a foolish recommendation. Toran followed this regime but suffered a repeat of the former adverse reactions and suddenly hanged himself after 15 days on fluoxetine. He was only 17 years old.

After Toran’s death, Maria had genetic testing conducted, which confirmed that Toran metabolised drugs slowly and had therefore been overdosed. Maria also established CASPER, an organisation where those bereaved by suicide help others bereaved by suicide (http://www.casper.org.nz/). Maria has told me that the national media have credited CASPER with a 20% drop in youth suicide and that it means more to her than anything else that her son continues to do good in the world despite not being here physically.

Maria wrote to the District Health Boards in New Zealand and found out that 8% of those who died and who had gotten a recent prescription for an antidepressant, had no diagnosis of any mental disorder. In the district responsible for Toran’s care, 75% of those under 18 who died had no diagnosis.

In New Zealand, psychiatrists and suicidologists have managed to convince the government that publishing information on suicides causes copycat suicide. She has reviewed the evidence for this, which is extremely weak, but it’s nonetheless a criminal offense for Maria to tell Toran’s story, punishable by a fine of up to $5,000 each time and a fine for the media of up to $20,000. These threats have not stopped Maria and she has had support from the media.

Maria sold her home to pay for Toran’s inquest when the doctors dragged it out over 18 days of hearings, thinking she would walk away because of the cost. She now lives in Dublin, in the home of another mother who lost her child to SSRI-induced suicide, Leonie Fennell, and has everything she owns in two suitcases.

There have been ten government enquiries into Toran’s death but, as in all such cases, the issue is not whether the child received a good standard of care but whether the psychiatrist departed from generally accepted practice. And of course, since the usual practice in psychiatry is terribly poor, most of the investigations found that Toran’s care was not a departure from usual practice. However, both the government and Mylan Pharmaceuticals have resolved that it is probable that fluoxetine caused Toran’s suicide.

Maria is still fighting to achieve justice and has persuaded the police to review Toran’s file to see whether manslaughter charges can be laid. She hopes that her efforts will be a deterrent, which could make other doctors consider that their patients may have a stroppy mother like her and be more careful. Maria has spent seven years on meticulously documenting Toran’s case learning everything she could about psychopharmacology, psychiatry, neurochemistry, genetics, randomised trials and anything else that could help not only her but also all the other parents that have stories similar to hers.

When I gave a lecture at the Department of Psychology at the Manooth University outside Dublin, to which Maria had invited me, another bereaved mother was in the audience, Stephanie McGill Lynch, who also lost her child to fluoxetine. Maria wrote to me:

“I know you agree with me that this has got to stop.” Yes, and this is why I have written this book. I won’t accept that doctors and drug companies push our children into suicide with drugs that have no benefits for them. I cannot see it’s any different to killing our children by pushing narcotic drugs in the street.

(First published in my book, Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial)